This paper is about

how a consortium of five Japanese companies (COJAAL: Consortium Japonais Pour L’Autoroute Algerienne) is undertaking to build a 399 km, six-lane, limited-access highway across northern

Algeria. The paper

starts with the bidding process,

the evaluation method and the structure of contracts that govern the construction of the project

on a design-build basis. Since the contractor is allowed to alter, and

therefore is responsible for, highway routing to a certain extent, the paper describes how this discretionary power was exercised to determine the final location

of the highway. The paper then goes on to outline organizational setup, physical and design parameters, procurement and logistics,

and construction execution plans. As of

February 2009, the contractor

is about 29 months into the project,

whose duration was originally set at 40 months.The

paper highlights events and/or issues that have had time impacts since its commencement in September

2006. Some sections of the project

have faced major landslides.Other sections

are being impacted by a shortfall

of critical materials such as crushed gravels for pavement. The contractor also experienced complications from having

to build a project to the French

standard when natural conditions in Algeria do not necessarily lend themselves to the French standard. Sourcing and mobilizing labor from out-of-the-country markets

in sufficient numbers and having

them work efficiently

on a stretch of construction sites extending over hundreds of kilometers have added to the task of coordination and control. As such, the paper represents an interim report on, and a case study of, managerial and technical challenges that an overseas

project of this magnitude and scope can present to the contractor, as well as approaches that can be taken to meet such challenges.

KEYWORDS: highway construction, design-build management, construction standards

1. INTRODUCTION

In September 2006 a consortium of Japanese contractors (Cojaal: Consortium Japonais Pour L’Autoroute

Algerienne) signed a ¥5.4 billion

design-build contract for a 399 km eastern section

of the Algeria East-West Highway, one of the largest

civil construction projects

ever to be undertaken by one entity in the history of the Japanese

construction industry.

The award

was

a

result of international biddings conducted by the Algeria Public Works Ministry

in January 2006 to build out a contiguous 1,200 km

East-West Highway from the Moroccan

border to the Tunisian

border. The

Ministry

divided up the Highway into three sections of approximately

equal size, with Chinese contractors coming out as the winners of the western and central sections. Of the six bidders who competed for the eastern section, Cojaal

bid the highest. Bid evaluation assigned 60 points to technical and 40 points to financial. Cojaal succeeded in tipping the scale largely on the strength

of technical merits that it earned for a crash construction program utilizing global

positioning systems, and contingency planning for the earthquake hazard.

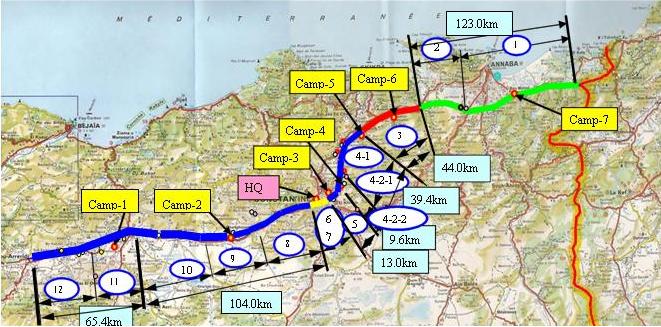

Figure 1.1 gives

an

outline

of

the

Project,

while

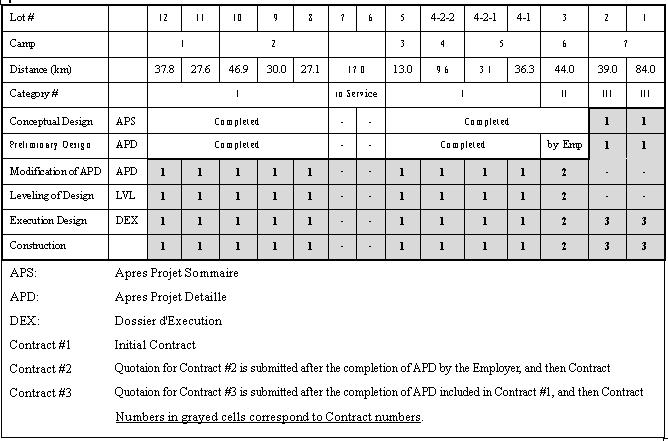

Table 1.1 details

the structure of contracts

as well as

how

each contract defines contractor’s

design-build responsibilities. Of particular note is the contractor’s right to propose alternative routes

over large stretches of the Highway.

Figure 1.1 Project Outline

Table 1.1 Structure of Contracts

As of February 2009, Cojaal is approximately 29

months into the 40 month project. In what follows, the paper describes how Cojaal set itself up to handle

this enormous undertaking, and what it encountered once the project got under way. As such, this is an interim report on managerial and technical

challenges that an overseas

project of this magnitude and scope

can present to the contractor, as well as

approaches that can be taken to meet such challenges.

2. HIGHWAY ROUTING

The ¥5.4 billion contract amount was introduced at the last stage of contract negotiations with the Employer as a

cut-off point for the aggregate payments that Cojaal is entitled to receive inexchange of completing a yet-to-be-designed Highway whose routes are subject to change.

The only exceptions are cost

and time associated

with variation orders,

force

majeure,

and

other

causes attributable to the Employer.

Preliminary studies by Cojaal revealed that moving

the Highway from its initial route through the coastal

mountains to

the edge of the coastal plains northward would eliminate tunnels

as well as high

bridges across ravines. These cost savings,

however, needed to be weighed against

impacting

towns and villages

along the alternative routes and having to spend time devising,

negotiating and implementing

mitigations.

In anticipation of this, Cojaal negotiated a special contract provision that compensated

the contractor for time and cost arising out of extended delays in

obtaining approvals.

When Cojaal accepted this “price ceiling,” it essentially took it upon itself the challenge

to choose

Highway

routes and to develop

subsequent design

details such that, barring force majeure and other

exceptions, the Highway

can be executed on time

and project cost can come

in below the price ceiling.

3. PROJECT EXECUTION

This Chapter summarizes how

the Project

was initiated and managed at site, highlighting issues

of time management as well as quality control.

The members of Cojaal recognized

that key success factors in this regard

are procurement and logistics (P/L) and design

management (D/M).

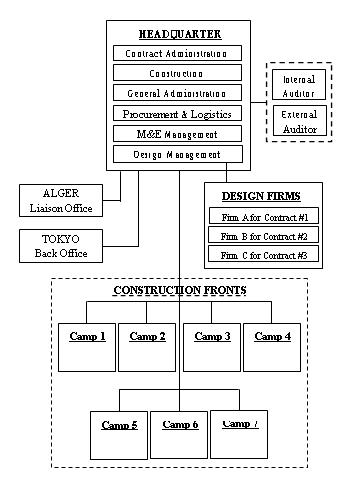

3.1 Organizational

Setup

Project

organization adopted

involves seven site offices, called “Camps,”each of which

is to construct a section of the Highway that varies

in length from 12.7 km to 123 km. The Headquarters (H/Q) coordinates, controls and integrates the activities of the Camps as shown

in

Figure

3.1.

Each Camp internally replicates the functions

that H/Q has, such as Contract Administration and Design Management.

Design

within the scope of Cojaal is outsourced

to internationally recognizedm design firms. The

design process is managed by staff dispatched from the members of Cojaal.

3.2 Construction Execution

The Campsexecute construction of the assigned work scopes independently, based on work budgets

and programs that have been agreed upon at meetings presided by the H/Q.

With the exception of Camp 7, each Camp is

operated by one member of Cojaal. For

instance, Camps 2 and 4 are operated

by Kajima Corporation

Figure

3.1 COJAAL’s Organization

alone. This setup gives each member company

managerial autonomy, allows aggressive application of proprietary technologies, and most importantly, provides

a strong incentive to achieve good results for the company,

contributing

to Cojaal’s overall success.

As Camp 7 was to commence last, it is operated by

an internal

joint

venture

where

the

members of Cojaal can pull together their experiences from their

own Camps and expedite work progress.

3.3 Procurement and Logistics

Timely procurement of plant, equipment and major materials is a prerequisite to on-schedule

work

progress.

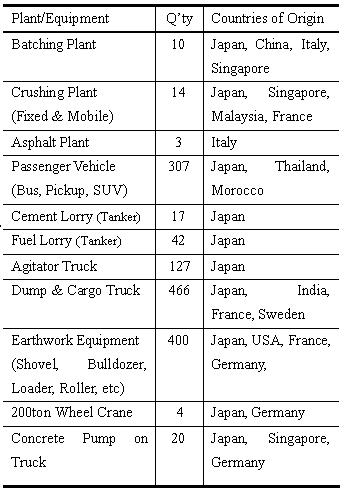

3.3.1 Plant

and Equipment Procurement

Since aggregates, cement concrete, and asphalt

mixtures shall be manufactured by Cojaal, all necessary plant and relevant equipment were globally procured early on. So were earthwork

heavy equipment, passenger vehicles and other

common

equipment.

In order to meet a demanding time-schedule, huge

volumes of cargo were rushed in the initial

stage to the Port of Skikda,

the closest and most convenient

port of entry Table 3.1 exhibits a procurement schedule of such major plant and equipment which were

purchase-ordered

to vendors during the first seven

months immediately after signing the contract. The countries of origin range from Japan, North America,

Europe to South East

Asia Table 3.1 Procurement Schedule

of Major Plant &

Equipment during the first Seven

Months

The total volume of plant and equipment shipped to

Algeria from various countries amounts to

110,000FT

during

this

first seven months,

out

of

230,000FT during 28 months until December 2008. The value of the

first

seven-month procurement exceeds 20 billion Yen, or 220 million USD.

The P/L

mission has been carried

out with diligent preparations and particular care taken to:

1) Purchase-order to plural vendors a single item at

a time to procure a large quantity in short period.

2) Manage

delivery of the items to warehouses

at original ports to effectively utilize

deck spaces of cargo vessels

3) Call

well in advance cargo vessels bound for or via Algeria, whose availability is quite

limited.

4) Make

up complete shipping/import documents to facilitate customs clearance.

5) Hire effective stevedores; experienced custom

brokers; and inland

forwarders to unload and transport the cargo out of the port in a timely manner.

6) Communicate well within the P/L team located both at H/Q, the consignee; and at Tokyo back office,

the shipper.

3.3.2

Materials Procurement

An initial assumption that major materials such as

aggregates, cement, reinforcing bars, concrete pipes, and

bitumen, etc., can be procured easily from local sources turned out to be inaccurate:

1) Aggregate

The planned Highway route provided distant

views on both sides of a number of mountains

being actively quarried, which led Cojaal to attempt to purchase from the operators of those quarries the necessary quality

and quantity of aggregates. This effort

was

given

up due to disagreement over the conditions

offered by the operators.

The second and adopted option was

for Cojaal to operate crushing plants at quarries

and produce the aggregates. However, some quarries turned out

after

some trials

to

produce limestone aggregates that did not meet the specifications in terms of Los Angeles Abrasion Test results.

The engineers

from the Camps and the P/L team collaboratively explored satisfactory quarries, and the last necessary quarry was identified only recently. This time-consuming quarry hunting has resulted, in part, in the procurement of a large

number of crushing plants as shown

in Table 3.1.

2) Cement

Since Algerian mountains are constituted primarily of limestone, ERCE, a government

agency, operates a number of cement factories. Although the quality is satisfactory, the quantity is not enough. As a result, cement lorries dispatched from the Camps routinely wait for cement loading

for several hours in a line at the

factories. Consequently, a cement

lorry can

makeonly one

trip for cement transportation a day, leading to less

stock in

silos than was planned.

This situation aggravates

in summer time when

production drops due to the “Vacance,”

similar to what happens in Western Europe. Some busy Camps have

responded

by stockpiling

cement in “Ton

Bags” in well

conditioned warehouses two months before summer vacation starts.

3) Reinforcing Bar

The specifications for the rebars are in accordance with the French standard,

which is unfamiliar to non-European suppliers. Thus, the number of foreign

suppliers that Cojaal can use

is limited.

It was fortunate that an international steelmaker operates a steel mill in Algeria, and that rebars using the French standard

were available locally through their official distributors.

The problem

was the handling of the rebars at the distributors’ warehouses. Poor inventory management has made it difficult to identify

rebar specifications such as

strengths and diameters.

Thus, the P/L

team

was

forced

to

procure

specified rebars from reliable Italian suppliers

at the beginning.

Similarly,

Cojaal

has

experienced

problems

with many other materials that were locally procured.

3.4 Design Time Management

Design time management is critical to the overall management of time for a design-build

project. When design is not finalized and fixed on time, subsequent activities

such as

procurement and construction can not be carried

out

according to schedule. Benefits of fast track or phased

construction often sought in the design-build scheme are

thus predicated on successful time management of the design process.

3.4.1

Design Information Flow

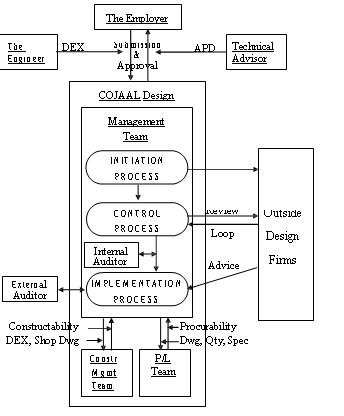

Figure 3.1 also shows Cojaal’s design organization. H/Q’s design management team and Camps’ design

team

collaborate with outside design

firms.

The Employer also hires his own design consultants

as “Technical

Advisor” and “The Engineer.” They

are the counterpart of Cojaal’s design

management team.

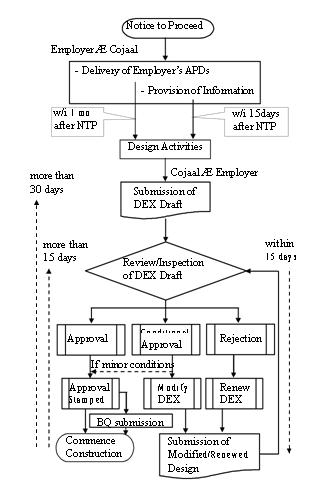

Figure 3.2 exhibits the flow of design information

exchange among the design-related organizations in case of LEVELING and DEX. The LEVELING

is the matter of “Technical

Advisor” and the DEX is of

“The Engineer” in the

Employer’s

organization. The design is finalized when the DEX is approved.

The DEX approval procedure is summarized

in

Figure 3.3. The

DEX

can

be

approved

in

a

minimum of 15 days if the Engineer

does not find in the

submitted DEX draft any major deviations from

the Employer’s requirements in the Contract

Figure

3.2 Flow Diagram

of Design Information for

LEVELING

(APD) and DEX

Figure 3.3 Flow Diagram of Approval Procedure

for

DEX

3.4.2 Difficulties in Design Time Management

Cojaal

has found it difficult to manage design time in

this Project. Uncontrollable and/or unexpected

events and

circumstances have affected the design process,

in more ways than Cojaal

ever expected. Approvals

of the designs presented to the Employer (the Engineer

and Technical Advisor) were anything but timely

or forthcoming.

The difficulties which Cojaal

has faced include:

1) Limited availability of original APSs & APDs,

2) Sparsely located original bore-hole

logs,

3) Environmental restrictions unknown to the

Bidder (prospective Design/Builder),

4) Technical Specifications particular to this

Project,

5) Unfamiliar standards (the French standard) frequently referred

to in the Specifications,

6) Inconsistency time-to-time in the Design

requirements and preferences,

7) Lack of prompt

Employer

responses

to

the Contractor’s submission,

8) Magnitude of the Project

9) Design Firms located outside

Algeria

10) Disagreements with

the

international design firms

11) Reconciling construction requirements with design requirements

12) Pursuit of cost effectiveness in the design phase under the price ceiling

13) Scarcity of experienced in-house design mamagers

14) Ruling French language

3.4.3 Design/Build scheme : from the Contractor’s View

Textbook arguments for and against the D/B scheme

typically look like the following:

1) The Contractor

can incorporate its innovative

technologies and constructability in the design,

leading to reductions in cost & time,

2) Overall project time can be reduced to

the extent that “Fast

Track” or “Phased Construction” is possible,

3) “Checks and balances”does not work well between the designer and the contractor because both functions are integrated in one entity,

4) The Employer needs to take strong control of project expenditures so as not to allow the cost

to exceed the budget, and so forth.The experiences by Cojaal, however, suggest

that benefits of design-build can vary greatly depending on

the following circumstances:

1) The

design/builder proposing to

utilize its innovative technologies for time/cost reductions often meets with resistance from outside design

firms because the latter are afraid of liabilities

that may

arise from

adopting such innovative technologies.

2) Design

time management is a complicated task, often leading to delays in design progress. In

such cases, the benefits

of fast track or phased construction are elusive.

3) The Employer has the ultimate

right to approve design and

construction, meaning

that

the Employer’s review and/or approval

rights affect all

activities of the design/builder. The degree to

which this relationship

can

work

to

slow

or

expedite project progress

may exceed contractor

expectations.

4. CURRENT ISSUES IMPACTING TIME

Of the events that impacted on-site

work progress since construction commenced, two things stand out: landslides and a shortage of aggregates.

4.1 Landslides

Part

of the Highway traverses an extended terrain characterized by limestone-marl formations. Cojaal

did not anticipate the degree to which

partially-weathered marl in this

area

is susceptible to

landslides. After excavation started on the tunnels

in this section of the Highway, construction stalled

in the face of extensive landslides around tunnel entrances and where

hillsides

were

cut

for

the project.

Mitigation measures included

moving the location

of tunnel entrances, constructing embankments or

driving long piles that can hold the weight

of marly

formations on the slopes above, and installing drainage

channels through the marl.

4.2 Shortage of Aggregates

Production of

aggregates

suffered not

only from difficulty of finding

suitable quarries but also from restricted supplies of explosives. The latter was

due to strict controls on the distribution of explosives for security reasons: regulations require

that any transportation of explosives

from the only source available near the western section of the Highway to the quarries be attended by armed official guards,

and all explosives be used up while the guards are in attendance

at the quarry.

This places severe constraints on the production of concrete and crashed

gravels

for

pavement,

and

limits the amount of blasting for tunnel excavation.

Cojaal is applying

for

a

special

permit

to

build

explosives stockpiles. The location of such storage facilities is still

being negotiated.

4.3 Construction Standards and Specifications

The Employer has adopted construction standards and specifications (CCTP) that are conceived along the French standard. CCTP not only

requires testing methods and performance measures that are unfamiliar to Cojaal,

but also imposes restrictions that

are often at odds with local conditions

in Algeria.

As a case in point,

CCTP discourages the use of limestone aggregates in the surface

course asphalt mixtures when in fact the only aggregates locally available in large enough

quantities are of limestone. The issue is insufficient hardness of local limestone.

As a result, a solution being proposed by Cojaal is to mix blast

furnace slag or hard

sandstone with

limestone aggregates to improve the abrasion/corrosion resistance.Cojaal continues

to

encounter

situations

where

it

finds

CCTP impractical or uneconomical, given

local conditions. Cojaal’s approach has been to devise

alternative means or methods that Cojaal deems to

be “equivalent,”

and

to attempt to convince the Engineer to adopt them. Cojaal is assisted in this

effort by a committee of experts formed

in Tokyo that regularly convenes

and

advises

on

technical

solutions.

4.4 Labor Management

Cojaal found that the Employer often had issues with the qualifications of subcontractors that Cojaal had chosen

to bring

in from foreign countries. It was also time-consuming

to

obtain

visas

for

imported labor.

Supervising groups of labor that are positioned far apart along the Highway has proven to be

demanding especially when the distance

involved can be 50 km or more. Workers who are rushed to move

between work locations using two-lane local highways

or partially completed roads are prone to engage in unsafe driving

practices, which have led to some fatal

accidents.

The task of on-site labor management

is often compounded by an

apparent lack of

sufficient supervisory capacity

on the part of the Employer. On-site

progress suffers and confusion ensues when

the Employer does not dispatch

someone to either attend

the testing or approve construction work that is ready for inspection.

5. CONCLUSION

Cojaal signed

on the ¥5.4 billion contract

for the Algeria East-West Highway with a full realization that

it

was crash

construction program

on

an

unprecedented scale. While

it may not have been typical for a design/builder to commit to a fixed sum

when the design was so incomplete, Cojaal regarded

the design-build features – including contractor’s

discretionary right to alter the Highway routes – as a lever with which to make the Project work as a

business proposition. It was a judgment call based on much analysis at the time and strong commitments from its members.

Working with a foreign government Employer on a

design-build project based on unfamiliar construction standards and specifications has so far been more than challenging; yet the members

of

Cojaal are bringing all their expertise and resources to bear

on the Project in order to succeed.